Baba scoops a fistful of yellow grains. He spreads his fingers, and lets the grains run through. They fall as grey dust, until they reach the sandpit beneath him and are reclaimed, ready to be shaped into moats and castles again. It is moon dust; Baba knows this. It looks like sand and feels like sand but sometimes when he digs quickly he sees the grey beneath, for a moment, before it yellows again.

Then the coughing starts. It’s not a normal cough. It’s more like he can’t breathe, and he coughs and swallows and sputters. Like a hand has gripped his neck.

In the schoolyard, the sky is faultless—a pristine, cloudless blue. Yet when he counts the drifts of breeze against his cheek they come every three, then five, then seven seconds, then three again. And he knows that above him the sky is not blue but actually black, that the breeze comes from air pushed through fans, and that he is not in a school like the one he had back home but a dome of cold steel and transplas panels.

“Tanya, come, look at this,” Baba beckons a girl in his class over. She eyes him with suspicion, walks over and stands with her hands on her hips.

“What?”

“Look at this,” Baba takes another fistful of sand and lets it fall through his fingers. “Look, it’s grey.”

“No it’s not,” she says, shaking her hand before turning away.

Baba looks again. It is grey. He’s sure of it.

When school finishes, Baba’s brother is waiting outside, eyes glued to his PAD as his thumbs tap frantically. Neither says a word—Timo’s eyes don’t leave the screen as their feet trace the familiar path back to the housing block. Baba sees everything though. The pristine, cloudless sky. Families smiling, chatting, talking about their days. The tiny birds which fly from one tree branch to another, and back again. The leaves which flutter every three, then five, then seven seconds.

As he walks, he takes huge breaths of filtered air. It never seems enough—as if his lungs aren’t filling up like they should.

Soon they are home. At the doorstep, Timo has to break his concentration for a second to look up at the door, which opens with a bleep. Baba’s eyes don’t trigger the locks yet; he has to wait another year for that, for when he’s ten. But he can go into and out of the shared courtyard whenever he likes, and as soon as he’s got his juice and taken his sandwich from the machine he goes back outside. There’s a porch, a small tree, a table with four seats and a lawn of perfectly manicured grass.

He hates the grass most of all. Of all the unreal things it’s the worst because it’s so clearly fake. A projection of green over a rubbery mat. At first, he thought the tree was real, because the trunk felt wooden, but when he tried to climb it his hands passed through air where they should have grabbed the branches. Still, if he lets his eyes go a little hazy he can sit on the porch and sip his juice and pretend he’s on Earth again, like the kids from the films kept from centuries ago.

“Why don’t we have the real sky?” Baba asks at dinner time.

“We have a sky,” his dad replies.

“But it’s just pretend. Why can’t we see the moon sky?”

“A day on the Moon is two weeks. A night on the Moon is two weeks. No one wants a two-week night. That’s why it’s pretend.”

“But it’s weird.”

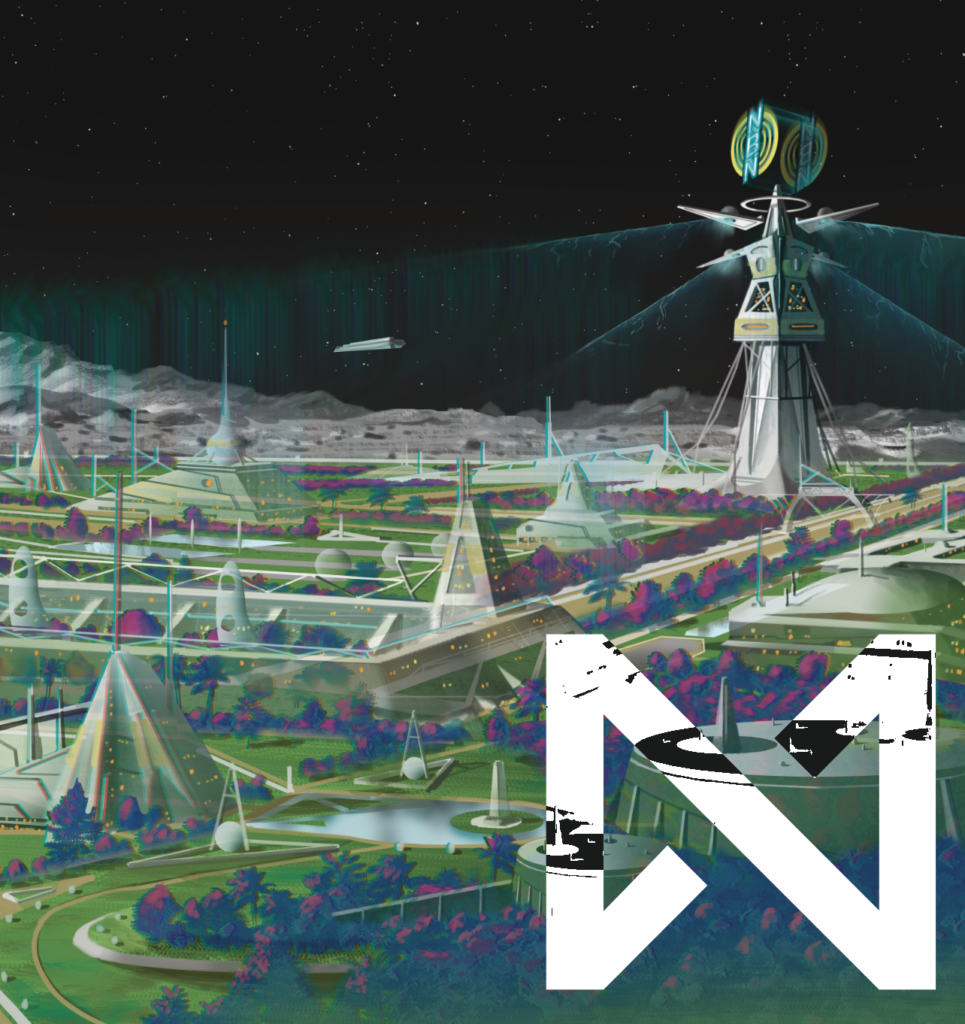

“I don’t think you realise how lucky you are. Most habspaces don’t have full AR. All the other children, they don’t get to go to school, or have an apartment like us, with a garden. They get grey corridors. They only play inside. But… since I work for R-Plus, we get to live here. And you know,” Baba’s dad leans in, smiling, as if they’re in on some great secret, “this LifeSim Suburb is the only one of its kind. The immersive tech here is the most advanced in the solar system.”

“Okay,” says Baba.

“I’ve got an idea. Timo, we’ll be back in a minute.”

Baba’s dad pushes himself up from the table and motions for Baba to follow. Timo ignores them—logged into GameNET, he’s unaware of anything else. Out on the street, Baba takes his dad’s hand, and they walk down the street towards the far edge of the habspace, away from the school, the shop and the pods which transport the grown-ups to the central hub where the NBN offices are.

“It’s funny. They’ve even put a road in here, even though there are no cars. You know why? Kids used to play out on the street. Now they can again. You see the white fence? That’s not actually there. But we found people like to walk through the gate, they like to know their gardens are theirs. I know it takes a bit of getting used to, but everything we’ve done here is to make this a more comfortable space for people to live.”

“Oh,” Baba nods, before a cough latches in his throat. He heaves in a lungful of filtered air, which seems to only make the coughing worse.

“You okay son?”

“I’m… okay…” Baba wheezes. He tries to slow down his breathing like his teacher taught him, until all that’s left is a tickle.

Within minutes they reach the end of the road, which turns to the left and carries on far into the distance, slowly receding to a thin line between two fields, before winding upwards into low hills, vivid green and spotted with trees. Sheep graze in the fields. It looks completely real, like he could keep walking for hours. What would be out there? What would he find?

“Look at this. It’s incredible. This is a screen. But it looks so real. And it makes you feel… calm, doesn’t it? At peace. You can smell the fresh air. Hear the birds.”

Baba nods. He can smell the fresh air. There’s something different about it to the air in the rest of the habspace, even though he’s only metres away. And he can hear birds, and see them too, flying to and fro in a nearby tree.

“This is what NBN is for. We make lives better. Coming here, living here. This is the future of Lunar existence.”

They stand looking at the view, getting lost in its intricacies. Baba notices a large bird, wings outstretched, gliding. He sees an airplane in the sky, a white trail like marshmallow in the distance. His dad is right, he realises. It does make him feel calm.

Then it all disappears, and it is suddenly night.

In an instant, the sky, the hills, the road, all gone. Everything grey-black.

Baba looks around. The houses are grey shells. The grass is a grey floor. The fence, the trees, the sun.

“Oh no. Oh no,” Baba’s dad begins to swear, his head whipping around frantically. “This isn’t right. We’ve gotta fix this.”

Down the street, someone screams.

Baba walks forward, to the edge of the dome. As his eyes adjust to the darkness, he sees shapes through the glass. Grey dust. The slope of a hill. A dip, the edge of which is ridged. In the distance, three tall cranes.

It is the first time Baba has seen it, except in photographs.

It is the most beautiful thing he’s ever seen.