1/

Space is a rarity on Luna. No matter where you go, you are crammed together in maglev carriages, in domes, in tunnels. Buildings squeeze shoulder-to-shoulder. Men breathe the same air.

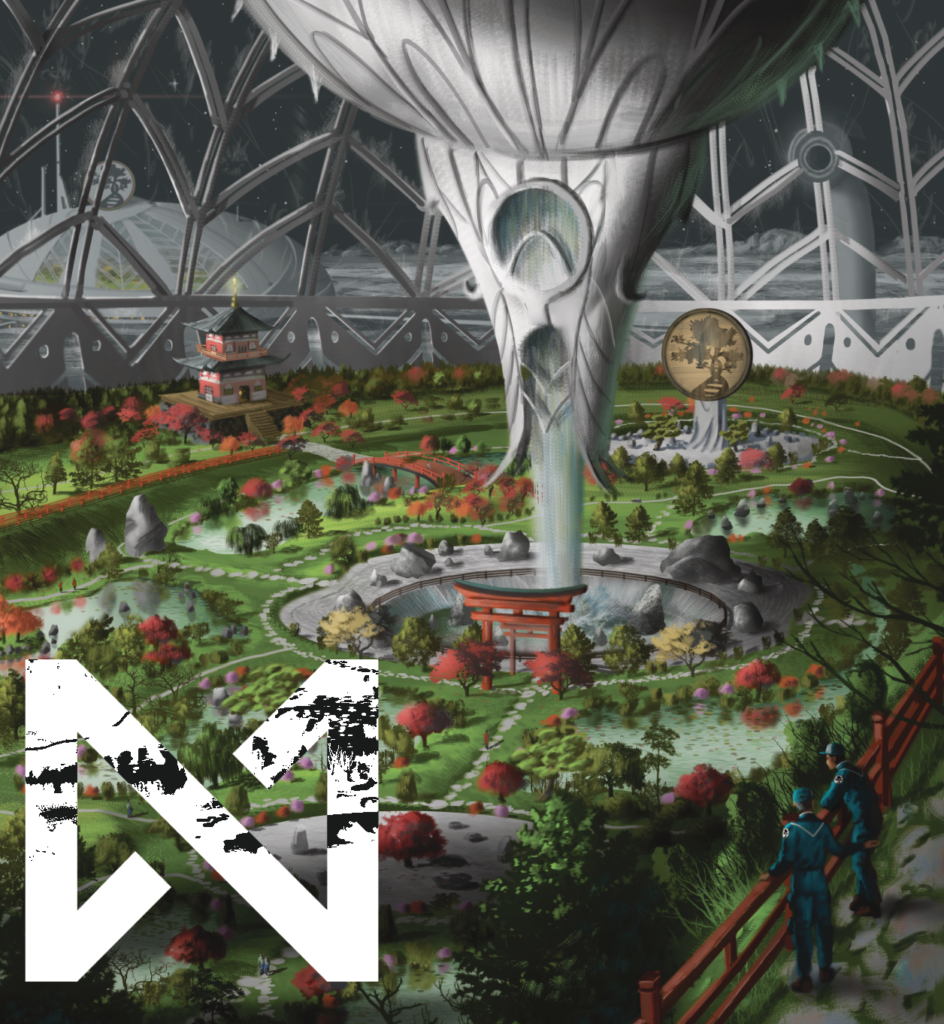

Not here. The new dome contained the largest contiguous greenspace on the Moon, with only a single two-story pagoda rising from the plane, giving a clear view of the Earth and the stars beyond. It was only open to Jinteki employees, and the most popular destination for those with clearance from Downstalk. But its most important utility was the benefit to the psychological well-being of those who worked in the facility below.

Director Kase sat on a bamboo mat on the second floor of the pagoda, overlooking the scientists walking between the red-leafed trees. The trees were their design, back when they were young and still gengineered things themselves; 34% more efficient under raw sunlight than regular photosynthesis, borrowing proteins from Rhodophyta to reach peaks evolution never could. But their proof of concept only worked under low gravity, and their work ended up only being used for ornamental plants on Luna. Even on Luna, most production relied on bioreactor and artificial lighting. Sunlight was a premium, only suitable for artisanal fruit for Lunar wine or the occasional microgravity pomello; high-end products where efficiency was explicitly not the point. Technically, it was brilliant, a pièce de résistance of gengineering, but practically it remained a novelty. The company moved on.

But in the long run, it didn’t matter. Today, forty years later, Kase ran their own division on the surface of Luna, reminders of their past planted in neat little rows, accenting against the chlorophyll-green grass below. Many projects had passed through their hands over those years, but for some reason the trees had always stuck with them. Maybe it was the first time they nearly tasted success. Maybe it was the first time they experienced crushing defeat.

Kase cleared their thoughts, focusing instead on the sound of rushing water from the central fountain. It no longer mattered. They were past all that now. Their gengineering days were behind them, and now they were responsible for hundreds of people, dozens of projects, each of which required their supervision and advice.

Which is why, despite switching off their PAD, they could still sense the reports piling up beyond the edge of awareness, all clamoring for their attention.

Kase sighed, and opened their eyes. They had to review these reports before their inspection of the lower levels later this afternoon, and further meditation wouldn’t do them any good. They switched on their PAD, and began sorting through unread messages.

Heinlein demographics. Twenty-six births today, sixty deaths, much of the latter in the retirement community. All of the babies were successfully registered in the Moonchild Longitudinal Study. Of note, three of the babies were second-generation Loonie. It had barely been two generations since the first child was born on Luna, and the long-term effects still had not been fully determined, though the current study had shown trends of increased polydactyly and agoraphobia, and decreased bone density, muscle mass and fertility. Humans were not meant to live in low-gravity, but that’s nothing a little gene shaping couldn’t fix.

And for everything else, there were shorter-term solutions. Their sales for myotube atrophy inhibitors and osteoblast supplements tracked tightly with tourism numbers, and those had nearly rebounded back to their pre-Fracture numbers. They tweaked the formula last quarter—not significantly more effective, but higher profit margins—and their advertising campaigns seemed to have pushed the new formula to at least 60% market share. They’d start phasing out the older formulations next quarter.

And finally, more tourists meant more IP violations. Ex-employees, disgruntled employees and unsecured servers all lead to intellectual property leaks, which were quickly snapped up by unlicensed biohackers for use in the underground party scene—which itself drove a significant portion of tourism. Aesthetic g-mods from official clinics hadn’t recovered to the same extent as the rest of the markets, and fieldwork suggested that the previous generation of gene-sculpting vectors had finally leaked, although this couldn’t be confirmed until a live sample could be obtained. Regrettably, those who frequented unlicensed clinics and those who visited the subsidized Jinteki health clinics were, for all intents and purposes, mutually exclusive. Kase signed off on a catch-and-release order, and also ordered an audit of the archival servers for any intrusion attempts.

Kase got up and performed a few stretches before heading down the stairs. Yamazaki stood waiting. The two nodded at one another and walked out into the garden together.

2/

The facility, in contrast to the garden above, was sterile. Clean. The mag-lift descended smoothly, quietly, into the depths, thousands of tonnes of lunar basalt silently pressing down from above. The Director wasn’t claustrophobic—it isn’t possible to be so on Luna—but as the lift descended past the genelabs and animal testing, to the deepest parts of the facility, Kase felt a sense of crushing weight.

It had no name. Officially, it didn’t even exist. Despite being a gaping red hole in Jinteki’s balance sheet, the Chairman kept it funded, believing that eventually the research there would pay dividends. Research that they would rather keep quiet. Life extension. Bioweapons. Population pacification.

Unofficially, it was known only as the Black Site. One of many, if rumors were to be believed, but it was the only one they’d ever know about.

Operations Manager Yamazaki, on the other hand, showed nothing. Not that Kase did either, as their ears began to pop, but they believed Yamazaki genuinely felt nothing. He ran the day-to-day functioning of the site, and living at the site was second nature to him. The lift doors slid open, and the two of them stepped into the antechamber in silence.

The alloy doors of the mag-lift closed as the two headed towards the locker cubes mounted into the walls and began to systematically empty their pockets. Kase put their PAD and a packet of tissues into the locker, which they locked with a thumbprint. They were about to turn around when they were interrupted by a voice, projected from one of the corners of the room.

“Yamazaki? Your ring.”

Kase looked over. Yamazaki was about to close his locker, but looked down at his right hand. “Right. Thanks.” He took off his ring and put it into the locker along with the rest of his belongings before sealing it shut.

The two stood in front of the entrance for a second as their bodies were scanned inside and out, and the massive plascrete door in front of them slid open, air gently pulling them inwards. They walked forward, into the corridor beyond.

As soon as the door shut behind them, the Director spoke. “Report.”

“Nominal progress on most fronts.” Yamazaki made a gesture, and a virt expanded in front of their eyes, following them as they continued down the corridor. “PTR VI completed their host range modularity system. Project Nettle: fundamental biochemical issues identified, and we are moving towards disposing the specimens. Staff have been reallocated to the Antisenescense Project, as we have found some long-term effects with Patient Zero that were not identified previously.”

“What effects?” Kase skimmed through the virt. Past the bleeding edge, where no profitable ventures lay, progress was slow. It’s not like fiction, where breakthroughs are expected and entire species and clone lines are developed in weeks. In the trenches, you could spend years of your life working on a single prototype.

“Abnormal chromatin aggregation. No symptomatic effects reported, but the biopsy sample is showing altered gene transcription, so we’d like to run it forward to see if it’s anything we have to be concerned about.”

They stopped in front of a door labelled OBSERVATION – BOTANICAL. “I would like to talk to the PI on Nettle,” Kase said, as the door unlocked with a thunk and slid open. “See where it went wrong.”

“I can arrange that.”

“Make it so.”

3/

The observation room was a large, circular room, with windows inset around most of the circumference, looking into the laboratories beyond. A third of the windows opened onto trays of seedlings on open benches; gengineers bent over, carefully manipulating roots and leaves within hydroponic baths. Larger plants sat on dollies waiting their turn.

But the rest opened on a different sort of laboratory. Scientists in containment suits moved slowly, air hoses and wires trailing up to the ceiling. Covered trays and plants in hermetically-sealed cylinders stood under lights and on benches, and to the side, glove boxes where specimens were opened and manipulated.

A suited scientist stood at the ready on the bench beside the window, her face somewhat obscured by the suit and glass. “Dr. Zielinska? Good to see you again.” Kase bowed.

Zielinska waved back. “Thank you for coming, Director.”

“Show me what progress your team has made this month.”

She nodded, and pointed to the first tray of plants on the bench, various grasses with yellow spots on their leaves. “We had been successful in expanding the host range of Ptr to rice and maize, but we’re having difficulty integrating all the changes into a single strain due to interference. This month we’ve designed and implemented a modular switching system, which detects the host species and expresses the appropriate invasion locus. Currently there’s a 10% loss of infectivity, probably due to the latency of the switching system, but we’re hoping to bring that down to 3% by the end of the month.”

She pointed to the other two trays on the bench, rice and maize, apparently, showing the same yellowing, one tray noticeably more severe than the other.

“Well done.” Kase says. “I’ll take a look at the data later. Cryptic transmission?”

“More difficult than anticipated. The team thinks that they might need to hook it into the host detection for the best results, but we can probably keep it below 200kb.”

“It’s not about size, it’s about host stress. Remember that it’s just a proxy.” Kase stared intently at the rice shoots. “Genomic stability?”

“We’ve had some issues with stability, but we’ve managed despite it.”

“Keep an eye on it. If it’s not viable on a multigenerational timescale, then—”

Red flooded the room. The emergency lights kicked on. Beneath the shrill alarm, Kase could hear the sound of the exit door locking. Kase flinched, and looked back at Yamazaki, whose eyes were darting about the room. The scientists behind the glass went still, heads moving in all directions. Zielinska merely looked down at her plants.

Yamazaki spotted his target and strode over to a wall-mounted console. A few taps, and the alarm went silent, but the red lights continued their pulsing. Yamazaki spoke to the console. “Security. What’s the issue?”

It took a second for the reply to come through. “Sorry sir, manual alarm triggered in Human-4. Everything’s reading fine, but they’re saying something about loss of pressure? We’re sending a team in, but that might take a while.”

On the other side, the scientists had silenced their own alarm. A few sat still, and some looked confused, but most were going back to their work.

Zielinska made what looked like a shrugging motion in her containment suit. “Breach in Human-4 sounds bad, but if it’s out we’re already dead. We’ll probably be here a while either way. So it looks like I have a bit more of your time than planned. You were saying about genomic stability?”

Kase shook their head, and went back to the discussion, under the pulsing red lights.

4/

Director Kase sat in the conference room with six of the department heads and Yamazaki, all looking at the single empty chair. It was getting late; the lockdown had let up only an hour later with an all clear, but emergencies required followup, and the heads were gathered here to debrief and discuss adherence to procedure. They all had to delay or cancel personal appointments, Kase included, but the only one late to this meeting was the head of Human Research, Alves. Kase passed the time in thought, looking out into the hallway through the conference room’s wide frosted windows.

Alves appeared at the door, slightly out of breath, and apologized whilst making his way to his seat.

“Now that we are all here,” Yamazaki began, as Alves took his seat, “we may begin. Earlier this afternoon, a scientist noticed that the airlock between Human-3 and Human-4 appeared to be improperly pressurizing. They thought that this was an emergency situation and triggered the manual alarm and sealant doors, and further investigation traced the fault to a miscalibrated pressure sensor. Thankfully, in this case, containment was not breached. A Henrietta Line assistant was dismembered in the sealant doors, and a replacement from HQ will take several weeks. How could we have prevented this situation?”

“We have standard operating procedures to inspect airlocks before use. Was this followed?”

“SOPs do indicate monitoring for abnormal gas consumption, and in this case the fault was only noticed because of lower-than-expected consumption. Though most of my staff report only checking for loose seals, as that appears to be a more common issue. I will instruct them to be more vigilant.”

Murmurs of assent throughout the room.

“We may also need to define clear limits on what counts as over and underconsumption, as this issue could have been corrected without a full facility lockdown.”

“Isn’t this issue with the sensor? Who was responsible for calibration?”

“The calibration of the sensors vary with the air composition pumped in through the cyclers. Usually the system automatically corrects for these changes, but SOP says to log the raw data to ensure that it doesn’t drift.”

“I assigned the logging duty to a new trainee, who neglected to do so this week. Though there was no observed trend in the raw data, that does not excuse me. I failed to train them properly. I will put more care into training new staff in the future.”

“Can this system be automated, to prevent errors like this from occurring?”

“Logging was meant to be a temporary measure. Something to do with the cyclers?”

“Yes. It was implemented last year as a temporary measure until the cycler replacements were installed. I will take it up with facility maintenance.”

“And how did your staff behave during the lockdown?”

“We had two junior staff members suffer panic attacks, but their seniors were able to calm them down. This is down from four during the last lockdown, and I will work to continue this improvement though the onboarding processes.”

Similar stories from around the table. Once everyone had said their piece, Yamazaki stood at the head of the table.

“Thank you all for staying late. Please make sure that your staff are informed of the changes required to ensure that this does not happen again. We all have things to work on.” The heads started to rise.

Director Kase spoke for the first time in the meeting. “Dr. Alves? Could you stay behind for a minute?”

Yamazaki turned to them quizzically, but Kase made a gesture and he left the room with the others. Soon, Kase and Alves were the only two in the room.

“The trainee who made the mistake.” Kase said, pulling open a virt, “Xiang, isn’t it?”

“How did you know?”

“Are you planning on sending him back up?”

Alves paused. “He’s a good kid, Director. I was hoping to avoid it, but I defer to your judgement…”

Kase continued. “I was the one who initially recommended sending him down. Top of his class out of Levy, glowing recommendations from his professors, and did well enough here to catch my notice.” They took a breath, glancing at the potted red bonsai at the center of the table. “I know he made an error, but a single failure shouldn’t be the end. We all make mistakes. The only thing we can hope to do is learn from them.”

Alves nodded curtly. “I’ll task him with clone maintenance for the next two months then. Give him time to think.”

Kase nodded back, and Alves left the room, leaving Kase deep in thought. But they started upwards, remembering their late appointment. It was rude to keep a guest waiting.